Every year around this time, for the last decade or so, I think about writing about 9/11, and I always tend to come up short. It’s not that there’s any shortage of memory or feeling there; like nearly anyone else old enough to remember that day — especially if, like me, you live in the shadow of NYC — I can recall where I was that day in more detail than I remember nearly any other day of my life, nearly down to the minute. The problem is moreso one of volume. So much has been spoken, written, filmed, and repeated that it feels like anything I’d have to say would be but a drop in the ocean. And yet, I can’t quite shake that day, and can’t quite shake the image that made the whole thing immediately and terribly real for me.

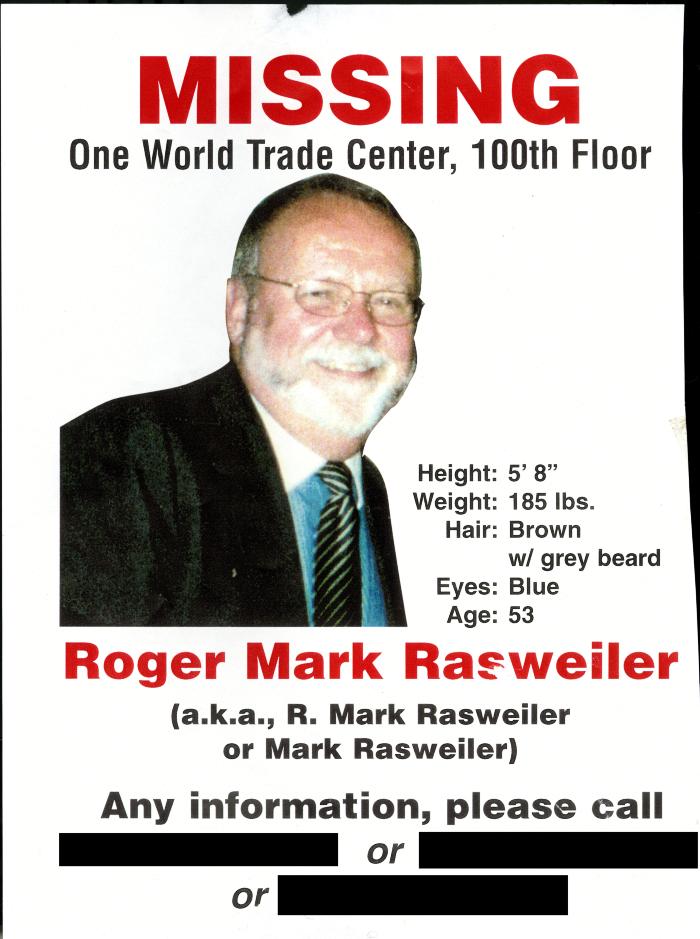

The photo that accompanies this post wasn’t chosen at random. The first time I saw Roger Mark Rasweiler (or his photo, at any rate) would’ve been some time around ten thirty on September 12, 2001. I was just getting on the train back home from work, and I saw a flyer just like this one in several of the train cars. I stopped to study the face, said a small prayer, and hoped against hope that this kindly-looking gentleman had just been detoured to Queens, or maybe a hospital somewhere in Manhattan or Hoboken. 36 hours after the towers fell, that wish didn’t yet seem as futile as it would in the days ahead, or as it did when I visited Union Square a week later, only to find the faces of the missing staring back at me by the thousands from subway cars, PATH trains, fences, and storefronts.

What does any of this have to do with photography? Maybe nothing at all. On the other hand, maybe everything. Those initial hours, after all, were a flood of words and images. The sheer volume alone would’ve rendered the lot of them overwhelming, but when you add the emotional heft — all the grief, confusion, anger and sadness with which every page and every frame was weighted — you’re left with something nearly staggering. It might just be me, but there was, and there sometimes remains, something in all of it that defies our attempts to cut it down to size, much less to make sense of it. Of course, it’s hardly the first or last time that would happen; we’ve had other catastrophes visited upon us before and since, and each time the end result is much the same: we’re practically struck dumb by the weight of history and documentation behind it all.

Time and time again, we hear the numbers of casualties thrown out when we discuss catastrophic events, be they the six million of the Holocaust, the three thousand of 9/11, the hundreds of thousands in the Boxing Day tsunami. Those numbers, by themselves, don’t illuminate much of the larger story; they reduce the victims to a single, faceless mass. How do we wrap our heads and hearts around something so enormous?

Something of the answer — for me, at least — is in that photo of Mark Rasweiler. Those single, still images invite us to step away from the whorl of emotion and motion; they provide a stillness, a point of reflection, in which we can pause and begin to attempt to understand. Just as importantly — perhaps even more importantly — they give us a sense of the human scale of inhuman events. Those three thousand weren’t a monolithic, homogeneous mass; they were three thousand individuals.

We were reminded again this year, as we’ll be in the years ahead, to never forget those three thousand. I don’t disagree. But as I enter my twelfth year with the memory of Mark Rasweiler, and the others who died with him, might I suggest we remember them one frame, one person, at a time?

Postscript:

This article appeared a month after the attacks, and is one author’s take on the Missing posters and spontaneous memorials that sprung up in New York:

http://www2.facinghistory.org/campus/memorials.nsf/0/79960486B7BD852385256FAB00664696

Image from the collection of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum